Logowanie

KOLEKCJE!

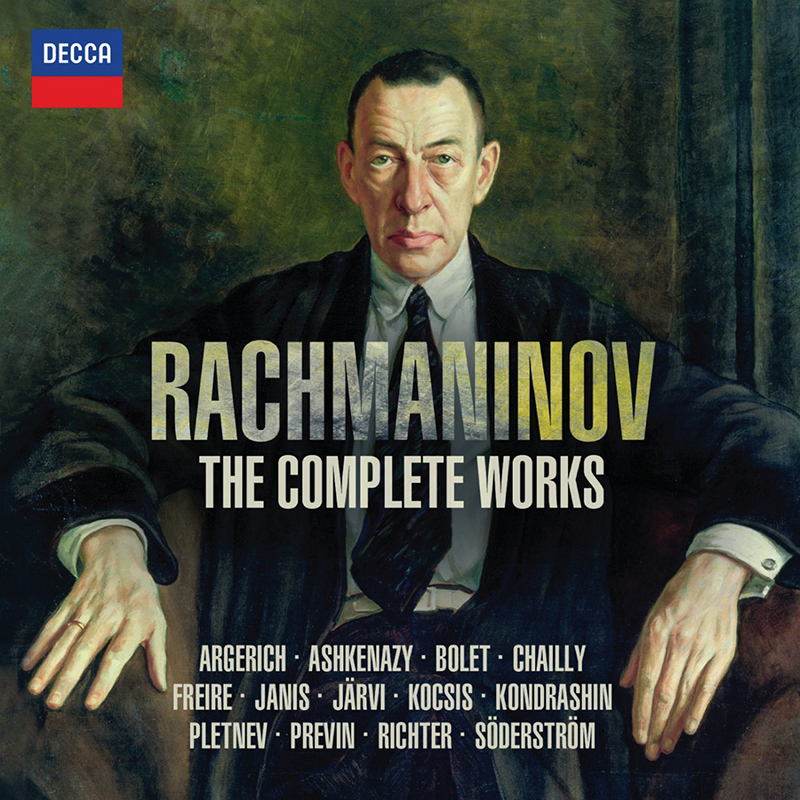

BACH, CHOPIN, LISZT, MOZART, GRIEG, Dinu Lipatti, Otto Ackermann, Ernest Ansermet

The Master Pianist

PROKOFIEV, CHOPIN, TCHAIKOVSKY, SCHUMANN, BEETHOVEN, Martha Argerich, Claudio Abbado, Giuseppe Sinopoli

The Concerto Recordings

The Collection 2

Jakość LABORATORYJNA!

ORFF, Gundula Janowitz, Gerhard Stolze, Dietrich-Fischer Dieskau, Deutsche Oper Berlin, Eugen Jochum

Carmina Burana

ESOTERIC - NUMER JEDEN W ŚWIECIE AUDIOFILII I MELOMANÓW - SACD HYBR

Winylowy niezbędnik

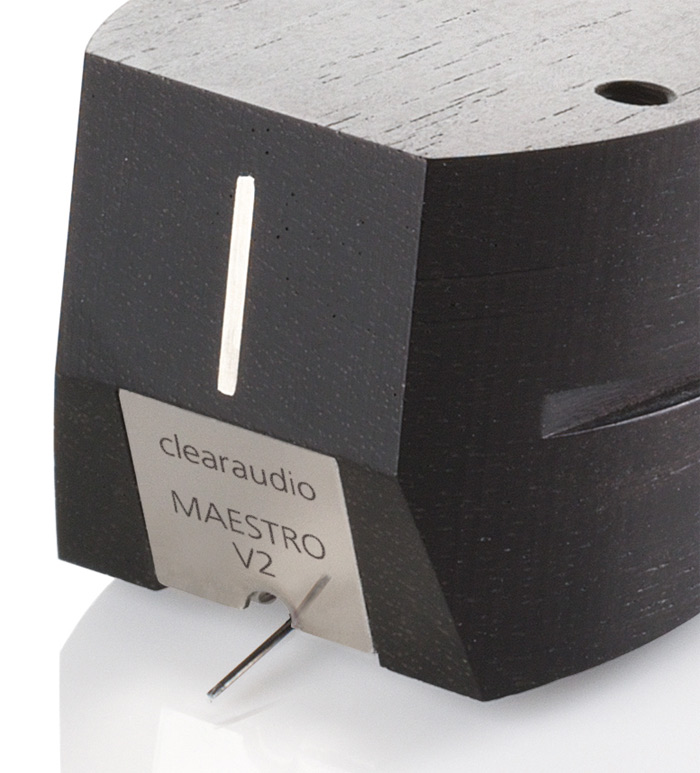

ClearAudio

Essence MC

kumulacja zoptymalizowana: najlepsze z najważniejszych i najważniejsze z najlepszych cech przetworników Clearaudio

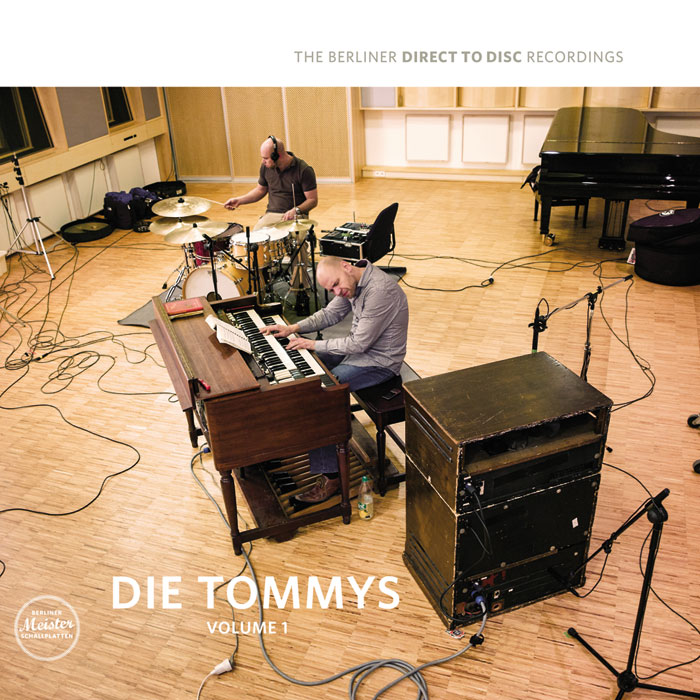

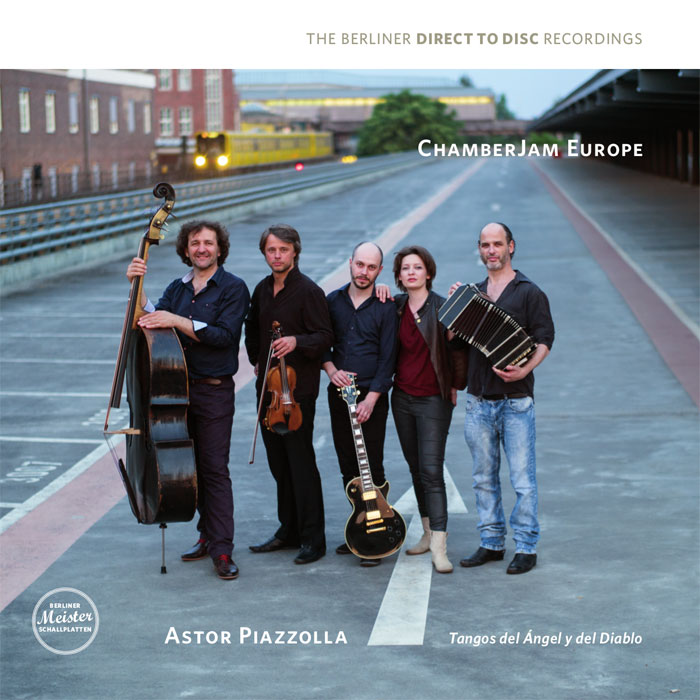

Direct-To-Disc

PIAZZOLLA, ChamberJam Europe

Tangos del Ángel y del Diablo

Direct-to-Disc ( D2D ) - Numbered Limited Edition

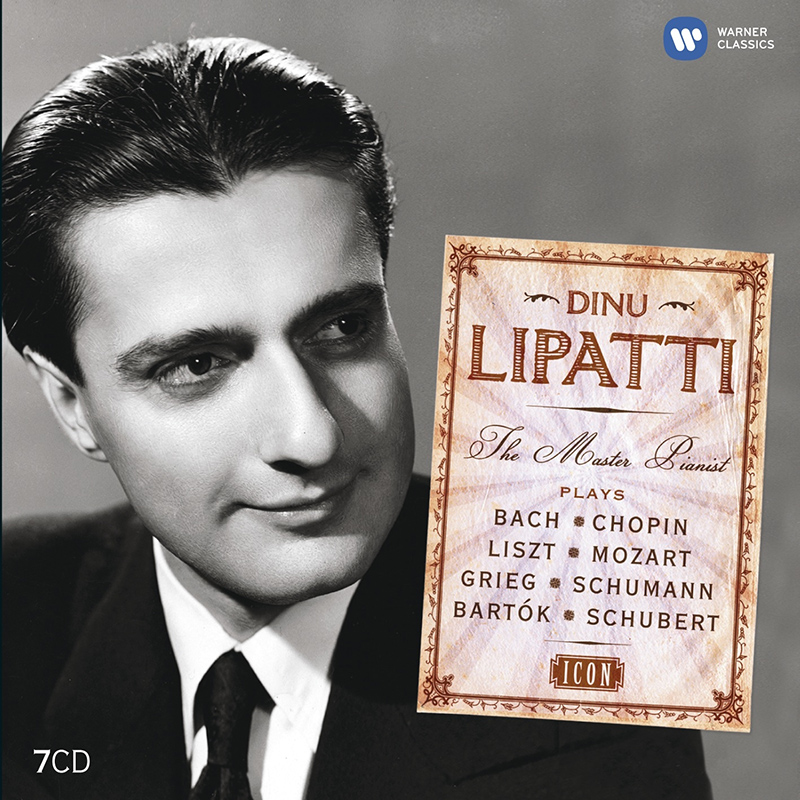

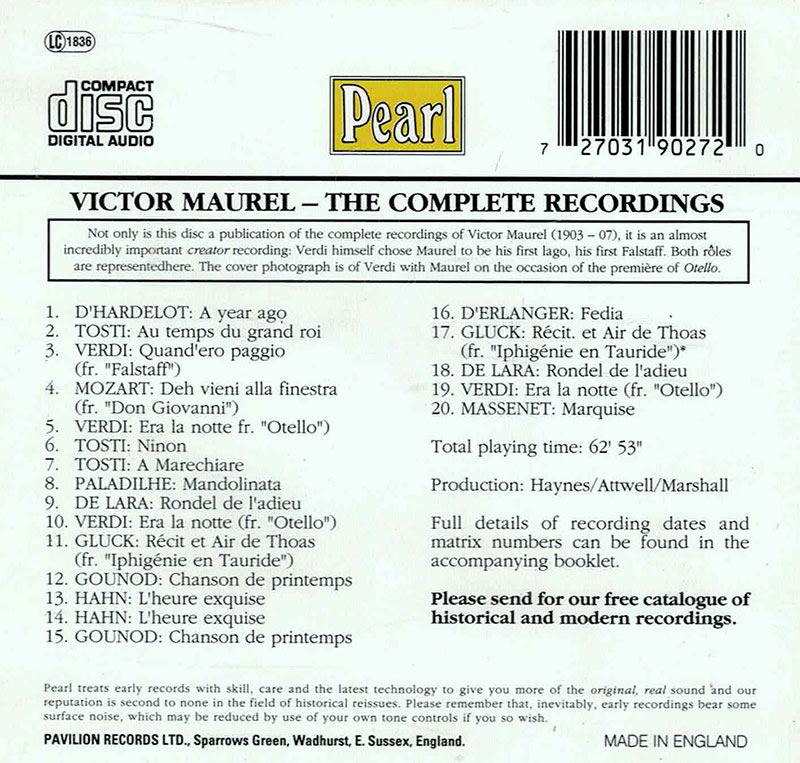

VERDI, Victor Maurel

Victor Maurel - Complete Recordings

- 1.A Year Ago - D' Hardelot

- 2.Au Temps Du Grand Roi - Tosti

- 3.Quand' Ero Paggio - Verdi

- 4.Deh Vieni Alla Finestra - Mozart

- 5.Era La Notte Fr. - Verdi

- 6.Ninon - Tosti

- 7.A Marechiare - Tosti

- 8.Mandolinata - Paladilhe

- 9.Rondel De L' Adieu - De Lara

- 10.Era La Notte - Verdi

- 11.Recit Et Air De Thoas - Gluck

- 12.Chanson De Printemps - Gounod

- 13.L'heure Exquise - Hahn

- 14.L'heure Exquise - Hahn

- 15.Chanson De Printemps - Gounod

- 16.Fedia - D' Erlanger

- 17.Recit Et Air De Thoas - Gluck

- 18.Rondel De L' Adieu - De Lara

- 19.Era La Notte - Verdi

- 20.Marquise - Massenet

- Victor Maurel - baritone

- VERDI

Na zdjęciu z okładki płyty, po lewej stronie - dumny starzec. Giuseppe Verdi. Obok - jego ukochany baryton, uczestnik premierowego spektaklu "Otella" i pierwszy "Falstaf". Na jego talencie i głosie Verdi oparł los dwóch osttanich, genialnych oper. I nie zawiódł się. Nagrania sztuki woklanej Maurela pozwalają nam doskonale rozumieć verdiowską wizję interpretacji ról w jegho operach. Niezwykle cenny dokument epoki, przykład estetyki dzieła operowego XIX stulecia. "The greatest of singing actors" was how the distinguished American critic W.J. Turner described Victor Maurel (18481923), when on a visit to London he heard the great French baritone sing Iago (first London performances of Otello, 1889). He went on to declare that Maurel's interpretation of the part made all others seem "limp and coarse". On a later occasion he commented thus on Maurel's version of Cassio's Dream, of which we hear two, similar performances on this disc: "His delivery was one of the most consummate pieces of vocal finesse this writer ever heard. That London audience literally broke into cheers at the end of it." The recordings, though made long after that occasion, confirm Maurel's supreme gifts in this field: through the crackle and the primitive 1903-4 sound, we discern a subtle, inveigling, superbly confident scoundrel as he retails the supposed musings of the sleeping Cassio. At the same time we hear a singer who over the years has begun to take a few liberties with the written score. A mordent has been added to the second syllable of "accanto", a trick later adopted by other singers of the role, and in a couple of places he sings an acciaccatura, a crushed note, below the actual note rather than above it as Verdi enjoins. But he is pretty faithful to Verdi's dynamic markings, even attempting the famous seven pianissimi at the passage starting "Seguia piu vago" More important than such details, Maurel gives us an Iago of insinuating strength such as Verdi obviously wanted. By the time he became the first Iago, at the 1887 premiere of Otello, Maurel was an acknowledged Verdi interpreter, and an experienced artist tout court. He was the composer's choice for the premiere of the revised version of Simon Boccanegra in 1881 at La Scala. By then he had already become one of the leading interpreters of Rigoletto, Renato and Amonasro. What was his path to this pre-eminence? He was born on 17 June 1848 at Marseilles, where he studied before moving to the Paris Conservatoire. He made his debut in 1867 in the title role of Guillaume Tell at Marseilles. By the following year he had already graduated to the Paris opera, where he appeared as Nevers (Les Huguenots) and as Luna, but did not return there until 1879 when he sang the title role in Thomas' Hamlet. Meanwhile he had appeared at La Scala from 1870, Covent Garden (1873-1879, 1891-95, 1904), where he was a great favourite, and the Metropolitan, New York (1894-99). Besides the parts already mentioned his repertory included Don Giovanni, Count Almaviva, Papageno, Assur (Semiramide), Sergeant Belcore, Nelusko, Rodrigo, Valentin, Mephistopheles, Telramund and Tonio, which he created persuading Leoncavallo to write the Prologue for him (how sad that he never recorded it). He was also the first London Telramund, Wolfram, and the first Covent Garden Dutchman. Maurel was renowned as much for his intelligence as for his voice. Many of his contemporaries, most notably Battistini, [on GEMM CD 9936, 9946 and 90161 had more beautiful voices. It was suggested by George Bernard Shaw that Maurel trained as an architect, but it doesn't seem that he would have had much time to practise that profession as he made his operatic debut by the time he was twenty. He painted and was a keen swordsman. He also lectured and wrote a great deal, including treatises on singing and works on the staging of Otello and of Don Juan. Shaw commented that "the role of lecturer was never better acted since lecturing began". That also points to Maurel's overweening selfregard which is confirmed by Turner who wrote of his powerful superiority complex. "The ego swam out of him at every performance and pervaded the house. Without doubt he was a little vain, a little pompous and not a little selfglorified. But what traits to serve as the foundations of the character of lago. And, as Desmond Shawe-Taylor commented in his profile of the baritone (OPERA, 1955): "We might add: of Falstaff too". For, of course, Maurel's last and perhaps most notable assumption was that of the Fat Knight in Verdi's final opera (premiere at La Scala, 1893). It received unanimous praise. Henderson wrote of "an astounding piece of theatrical virtuosity performed with perfect poise ... It must be recorded that his Falstaff is one of the great creations of the lyric stage His posing and facial expressions are the essence of comedy, and he makes every measure [bar] of the voice part throb with meaning. It is a superb, consistent and thoroughly artistic piece of work." Maurel went on to sing the role in Paris, St. Petersburg, London, and at the Metropolitan. How we would like to have a permanent record of the way he tackled Falstaff's two monologues. All that exists - and remember Maurel was 59 when he made the disc - is the brief solo as he attempts to seduce Alice Ford- "Quand'ero paggio". It is a unique souvenir of a creator's performance. Maurel sings it three times as he well may have done on the stage since the solo lasts little more than a minute. Each verse concludes with a burst of applause from a studio audience, a nice touch in those days of spontaneous happenings at sessions. This ready appreciation by a studio claque provokes Mantel to ever greater flights of verbal ingenuity and tonal variety, but the rhythm is kept surprisingly exact. Perhaps the most flexible and subtle performance of all is the third when Maurel resorts to a French translation: "Quand j'etais page du Sire Norfolk, j'etais si mince, que je flottais Diaphane mirage porte par la brise volage. J'etais alors a l'aube du bel age, j'etais un frele damoiseau; j'aurais pu me glisser a travers un anneau. Quand j'etais . . ." Another contemporary witness, Maurel's soprano colleague Emma Calve, [on CDS 94821 wrote in her autobiography that Maurel was "a man of genius" adding that: "His dramatic gift was so extraordinary that it dominated the mind of those who saw him, and almost made them forget his voice, which was, nevertheless of an unusual quality, full of colour and exceptionally expressive." By the time he came to record his precious few discs, all included in this new collection, it had obviously lost some of its freshness and resonance, but the warmth and individual colour can still be discerned. Aside from the Verdi items, a free but persuasive version of Giovanni's Serenade (described in New York as "a performance of marvellous lightness and grace", and a somewhat rough and ill-recorded account of Thoas's fiery offering from Gluck's Iphigenie en Tauride, he confined himself mostly to the ephemeral songs of his own day. The best of these is Hahn's recently composed L'Heure exquise in which Maurel employs his refined mezza voce to good effect and shows his ability to fine down his tone to a whisper. Paladilhe's charming Mandolinata is done with an appropriate lightness of touch incorporating little chuckles. In the items by Tosti, Guy d'Hardelot and Frederic D'Erlanger (Maurel created the part of Mathias in d'Erlanger's Jjuif Polonais), among the most popular purveyors of trifles at the time, you can almost see the elegant baritone delighting in small touches of individuality and the exemplary diction which doubtless pleased his many admirers at recitals and soirees. About the time of his recordings a contemporary witness, Albert Spalding, gave a keen and frank description of Maurel at this late stage in his career, which well applies to the records: "His voice had gone threadbare, but the majesty of an undying art was still there . . . After all these years, it is Maurel's portrayal of the naked villainy of Iago, the sophistical and Rabelaisian philosophy of Falstaff, the elegant and unscrupulous licentiouness of the Spanish Don that I recall each time I hear this music. He sang also a little song by Massenet, a rather cheap and sugar-coated morsel by Massenet [included on this CD] in which an old gallant recalls to his Marquise when and where she wore a dress of white satin. Maurel whispered this not too distinguished text with a kind of magical subtlety that was transfiguring ... " Maurel's last stage performance was in 1909 when he performed in Gretry's Le Tableau parlant, with Beecham conducting, after which he took up a new career as a teacher in New York, emerging from time to time to give what a critic called "entertainments" at the Carnegie Hall. His autobiography Dix ans de carriere was published in 1897, and reissued in 1977. ALAN BLYTH